Senamile Masango - Not Your Everyday Nuclear Physicist

- Reinvented Magazine

- Jun 11, 2020

- 5 min read

Written By: Rebecca Mqamelo (Guest Writer)

From teen mom to nuclear physicist – Senamile Masango is a shining example of how success is a non-linear process. Self-confidence, support, and hard work are the key, she says.

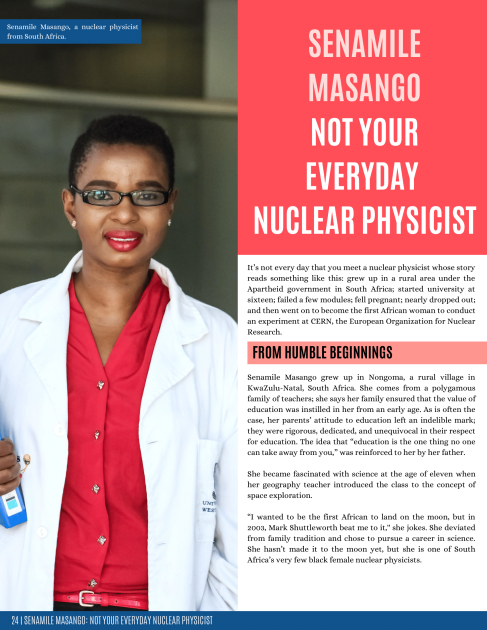

It’s not every day that you meet a nuclear physicist whose story reads something like this: grew up in a rural area under the Apartheid government in South Africa; started university at sixteen; failed a few modules; fell pregnant; nearly dropped out; and then went on to become the first African woman to conduct an experiment at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research.

Senamile Masango’s story exemplifies the idea that success comes in different packages and through circuitous routes. Her journey of hardship and resilience is an inspiring lesson for us all. In speaking to her, it becomes clear that it’s not where you come from or even what happens to you that defines who you are – rather, it’s who you choose to become that really matters.

From humble beginnings

Senamile Masango grew up in Nongoma, a rural village in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. She comes from a polygamous family of teachers; she says her family ensured that the value of education was instilled in her from an early age. As is often the case, her parents’ attitude to education left an indelible mark; they were rigorous, dedicated, and unequivocal in their respect for education. The idea that “education is the one thing no one can take away from you,” was reinforced to her by her father.

She became fascinated with science at the age of eleven when her geography teacher introduced the class to the concept of space exploration.

“I wanted to be the first African to land on the moon, but in 2003, Mark Shuttleworth beat me to it,'' she jokes. She deviated from family tradition and chose to pursue a career in science. She hasn’t made it to the moon yet, but she is one of South Africa’s very few black female nuclear physicists.

A non-linear path

Masango started school when she was four years old, which means she began university at the age of sixteen, two years earlier than her peers.

“I grew up with a very strict father,” she says. “For me, university meant freedom.” Navigating this freedom at a young age introduced numerous challenges for Masango. One of her biggest regrets is that she never had female mentors in the STEM track when she was starting out her journey as a scientist. “There were classes where I was the only female in my undergrad. I wish someone had been there to guide me.”

She reflects that she made many mistakes along the way. “I failed a few modules, I couldn’t finish my degree, and I also ended up pregnant.”

For many young women in a similar position, these hurdles might have meant the end of their academic pursuits. In South Africa, only 15% of university students make it from their first year all the way through to graduation. Unsurprisingly, the highest failure rates are in maths and science programs.

Masango experienced both failure and a major life event, but instead of quitting, she chose to persevere. She says the support of her family during this time was invaluable. She needed that support some years later, when her daughter was tragically killed in a car accident on her very first day of school. Nevertheless, she persisted.

Breaking the glass ceiling in science

In June 2017, Masango made headlines when she became the first African woman to conduct an experiment at CERN, the world’s largest particle physics laboratory. This is where you’ll find the Large Hadron Collider – a 27 km long particle accelerator where high-energy particle beams travel close to the speed of light and are made to collide with each other.

Masango and her team were studying the isotope selenium-70 in order to understand how its nucleic shape relates to its energy levels. She was the only woman on the team, although she marvels at the diversity that was present.

“This was also the first time an African institution had proposed an experiment at CERN. Most of us came from rural areas. We didn’t do our undergrads at UWC (the University of the Western Cape) and instead started at places like the University of Zululand, the University of Venda and Fort Hare – all historically disadvantaged institutions.”

Paving the way forward

Masango has strong opinions about what needs to change in order for more girls to succeed in STEM careers in South Africa.“As a country, we’re talking about the 4th Industrial Revolution. But first things first – we must fix our basic education. There is no way that we will develop without sorting out the education crisis,” she says. Masango’s sharp attitude about the state of public schooling in South Africa is well-founded. In 2014, the World Economic Forum ranked South Africa last (144 out of 144) in the quality of its maths and science education. In 2015, a World Bank report found that only 35% of Grade 6 learners were numerate at an acceptable level and the figure fell to a shocking 3% for Grade 9 learners.

Masango attributes this deplorable state of affairs to two things: inadequate teacher training and the lack of comprehension that sets in early when one is compelled to study in anything but one’s own mother tongue.

“Maths and science need to be taught in a student’s home language,” she says. “Countries that do well in maths and science are countries where children learn the subject in their own language. We must revisit our language policies.”

Many subjects are also taught in such a way that students are often left confused, rather than enlightened. Teachers simply aren’t well-versed in the subjects they are hired to teach. The 2015 World Bank report found that only 60% of people teaching mathematics in primary schools in South Africa could pass a test for the subject at the level at which they were teaching.

Masango’s vision is to use her foundation, WISE Africa (Women in Science and Engineering in Africa), to help girls excel in math and science. “I want to raise money to build my own mobile science labs. Limpopo, KZN, Eastern Cape – these are all deep rural areas where there is no infrastructure for teaching a subject like science. Students are being tested on ammeters but have never even seen one. Imagine learning chemistry if you’ve never mixed anything!”

In a country where government support for public schools is sorely lacking, it is initiatives such as this that promise to usher in the next generation of female scientists. Masango’s determined attitude of “paying it forward” might just be the catalyst that makes a difference in another young scientist’s life.

A circuitous path to success

In a world where success is often misconstrued as a linear path that leads to happiness and wealth, Masango’s journey is a reminder of the myriad ways that success is attained. Perhaps she defines the norm, in fact, when it comes to that mythical “road to success” – it’s more like a messy footpath, with detours and unexpected pauses along the way. It’s never straightforward. And it certainly isn’t easy.

Resilience is what really sets “successful” people apart from the rest. It’s that ability to face trying circumstances and relentless opposition, yet still take ownership over who you want to be.

Masango sees self-esteem as a vital factor in attaining one’s goals. Self-esteem, or basic confidence, tends to be overlooked in technical fields where words like “resilience” and “confidence” are overshadowed by accolades and outward excellence.

“Once your mind is right, there is nothing you can’t conquer. Science is challenging. You have to believe in yourself, be committed, work hard, and ultimately love what you do.”

For someone whose story might so easily have unfolded in other directions, Senamile Masango is proof yet again that circumstances don’t define your journey. Your choices do.

.png)